Introduction

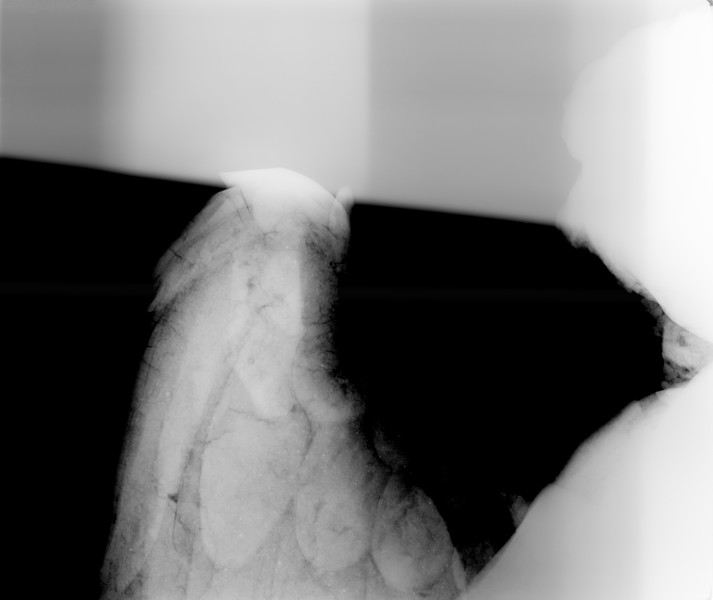

In addition to stylistic differences, the stucco decorations in the sanctuary also differ in the technical procedures and materials used. Certain of these cases show that several craftsmen could well have operated within the same workshop, not just simple apprentices or pupils, but artists with an already formed personality who also worked at different moments. In the decorations of the choir – which are due to Alessandro Casella – we see, for example, differences in the realisation of facial features, in the treatment of wings, drapery and hair (Fig. 1, 2), and looking behind the figure of God the Father, above the main altar, one can see the head of an angel that belongs to an earlier decorative project (Fig. 3, 4, 5).

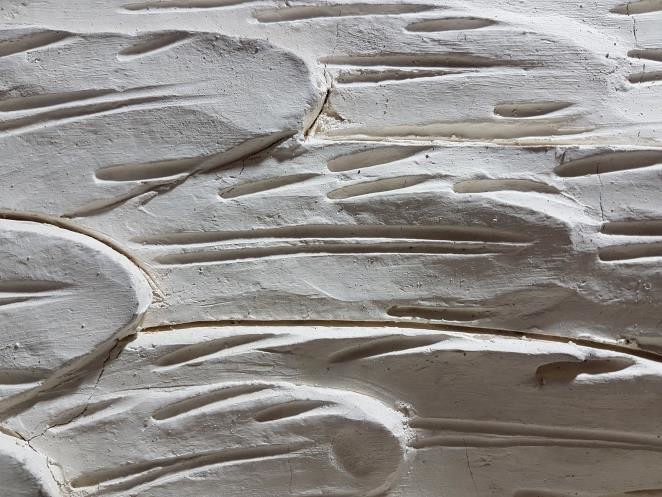

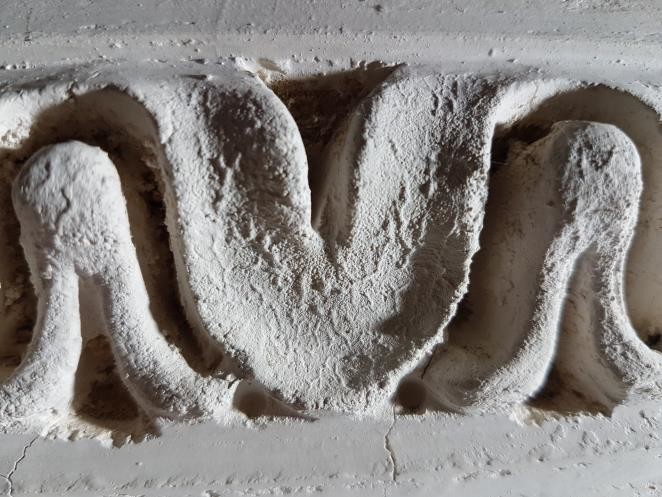

As in other works by this artist and workshop, the interventions of other workers, whose presence is documented on several occasions, is evident. Although they used similar materials and technical procedures, they show distinctive traits. The work of the master is recognisable in the larger figures, in the way the volumes of the drapery are constructed with extended smooth surfaces, and in the setting up of the anatomical construction. The interventions of one or more masters with less expressive force can be identified in the minor figures, which are more awkward and less harmonious. In any case, these are works of high quality, testifying to Casella's ability in managing the site and the high skill of these masters in modelling the mortar rapidly and with freshness. Among the common characteristics in these works we can see the strength of the deeply hollowed volumes, the smoothness of extended surfaces (Fig. 6), the effectiveness of the spatula strokes in working the finishing layer, and the dynamism in posing certain figures. The mastery of Casella and the sculptors close to him is equally visible in the realisation of the purely ornamental parts, in the numerous garlands of flowers and fruit that enrich the decoration of the vault and the tympanum of the high altar, and in the whorls of the entablature, which in the choir achieve a balance and fluidity of rare beauty (Fig. 7).

The stuccos are made with supporting structures of stones, bricks and roof tiles of various sizes, bedding and body mortars of lime with differing percentages of gypsum and sand of varying granulometry and mineralogical composition, then a finishing coat of lime and marble powder, and finally a lime wash applied with a brush. The reinforcements and anchorages are made with metal brackets of various sizes and in some cases also with materials such as twine, cordage or plant fibres. The greater and more pronounced the projections of the modelling, the more complex is the stratigraphic succession of the different parts. The gilding, particularly present in the choir, and the only polychromy - visible in the angels in the background of the high altar - are probably the result of later interventions.

Internal structure and body mortar

The body mortar is composed of lime and rather fine aggregates, with an unusual dark yellow-ochre colouration, resulting from the presence of a clayey material, rich in iron oxides, and red porphyry sand from Carona, mixed with the more common quartziferous material (Fig. 8). This particular mixture, not observed in other works by Casella, may have been chosen to obtain a preparatory layer that, thanks to the considerable water-retention capacities of clayey materials, would dry slowly, thus favouring workability. Unfortunately, this ability to retain water made the iron of the reinforcements and anchors more vulnerable, susceptible to oxidation and the related increases in volume, ultimately leading to the severe decay phenomena still visible today. The thickness of the mortar is substantial, up to three or four centimetres, however the composition is not always the same: analyses have revealed the addition of gypsum in the decorations of the nave, in the upper part of the counter-façade and in the angels of the transept. In the latter case, gypsum was added to the lime to prepare a particularly strong bedding mortar, found only on the back of the wings where the body layer connects to the masonry of the pilaster.

In the body mortar of the saints in the side chapels, substantial quantities of plant fibres are present, used in the thin and very projecting parts of the modelling, such as the tongue of the dragon of St Margaret or the clasps of the stole for St Gregory (Fig. 9). The addition of this material achieves numerous advantages: reduced weight and greater elasticity in the mortar, less loss in volume during drying. Other plant fibres, bundled like cordage, were found in the wings of the angels above the entablature of the counter façade (Fig. 10). Here, this was probably used to bind the parts of the supporting structure, such as roof tiles and flat stones, over which the body mortar was laid (Fig. 11). The metal reinforcements, on the other hand, are largely made up of the usual iron rods, but lacking the fabric covering that was generally used to facilitate the adhesion of the fresh mortar, as well as for isolating the iron from moisture, and so reducing risks of damage from oxidation. In some cases, the rods were joined together using thin wires or twine, singly or in small skeins. The instability of the most pronounced projections, observed in several parts of the decoration (such as in the blessing arm of God the Father at centre of the main altar tympanum, and the garlands of the vault around the window) can probably be largely attributed to these weaknesses in execution of reinforcements. The same imprecision (in this case perhaps the result of a pentimento in progress) is found in the armature of the two large angels holding a scroll at the base of the tiburium: here, the imposing mass of the figures is well secured to the masonry, but the progression of the main skeleton in metal is completely detached from that of the arms (Fig. 12, 13). Radiographic investigations show the presence of the same problem in other figures. On the counter-façade, in the right arm of St George, for example, the bend of the iron rod and the movement of the limb do not align: the body mortar covers the reinforcement unevenly and causes structural instability. Also in the dragon and hand of St Augustine, the iron elements were connected rather casually. Such singular and free use of supporting armature is again evident in the angel on the left-hand side of the transept, near the choir: the irons of his left fingers are not joined to the rod of his arm. It can thus be assumed that the stuccatore inserted the finger pieces when the hand had already been roughed out. This technique allowed the artist to work without careful pre-structuring of the sculpture armature, and to make substantial changes in the modelling in progress (Fig. 14, 15). Investigations with the cover meter revealed the very limited presence of the iron elements normally used in anchoring decorations to the masonry, relying on a single nail, for example, in the large rosettes of the sub-arch. The total and hardly comprehensible absence of a metal skeleton was also observed in the wings of the transept angels, which have an important development (Fig. 16, 17): perhaps, in this case, Casella could have used materials undetected by radiographic technique, such as wood or plant fibres. Various anchorages are instead visible at the back of other strongly protruding elements, consisting of assorted materials such as nails, rods, iron wires or string, roughly gathered together (Fig. 18, 19, 20).

Finishing

Given the absence of covering washes, we can recognise the usage of tools in finishing the surface (Fig. 21). In particular, the parts attributable to Casella and collaborators show a mastery of workmanship and expressive immediacy of rare quality (Fig. 22). The mortar, mostly composed of lime with a low percentage of aggregates (essentially finely ground marble powder), is spread in varying thicknesses, from just over a millimetre to almost half a centimetre (Fig. 23). The mortar is applied quickly, almost flowingly, without insistent working, although leaving numerous marks from the spatula, and even the fingers of the artisan (Fig. 24). The finish has a greasy to pasty consistency, and with the exception of the upper part of the counter-façade and the nave, generally shows only slight cracks, leading to the assumption that an organic material would have been added to prevent or reduce cracking1. The minute and dense incisions of the fringes and the floral decorations of the stole of St Augustine, the orderly plumage of the wings of the transept angels, as well as the edge-like sharpness of the Prophet eyelids, show how this material allowed Casella to express his skills as an expert sculptor (Fig. 25, 26, 27). The quality of the details, however, is not always uniform. The cases of lesser formal expertise frequently correspond with poorer qualities of material, as in the angels on the upper part of the counter-façade: here, in addition to deep and extensive cracking in the finishing mortar, the anatomical construction of the figures is weaker and the development of draperies seems incoherent.

The processing of the finishing layer concluded with a brushed application of lime wash, in some cases rather thick and full-bodied, which served the artist in regularising the surface imperfections left after the rapid modelling.

The decorative parts were all executed in situ; the sole elements identified as external to the specific modelling are the beads of the robes of the Prophets, and also the small fruits of the ornamental garlands, prepared freehand and then applied. In these we can see the care in execution of the surfaces, using short strokes of the spatula to render the rippling or roughness of the fruit skin (Fig. 28). Unfortunately, the application of these decorative elements - as well as the garlands and volutes - on an insufficiently roughened surface has later resulted in their detachment (Fig. 29). The serial elements of the cornices, on the other hand, were made using moulds of various sizes (Fig. 30, 31).

On all the stuccos, pictorial detailing done with a black pigment and brush could be observed. The pupils of the eyes, the tassels of the fringes, the pages of a book or the folds of a drapery are often emphasised with a dark colour to give greater volumetric prominence to the modelling (Fig. 32, 33).

Tiburium cupola

The body mortar for these decorations, consisting of a greyish mixture with little binder and poorly selected aggregates, has since suffered from salt crystallisation, leading to extensive and deep decohesion. The material impoverishment is so extensive that one can assume a massive use of gypsum as a binder: this would have been extensively weakened by the numerous water infiltrations, in some parts so severe as to completely wash away the surfaces (Fig. 34, 35, 36, 37). The workers’ inexperience in placing the anchoring nails, their small number and inadequate shape, have also contributed to detachment of large parts of the modelling. Some of this damage has occurred fairly recently, leaving remains resting on the cornice at the cupola base (Fig. 38, 39).