Introduction

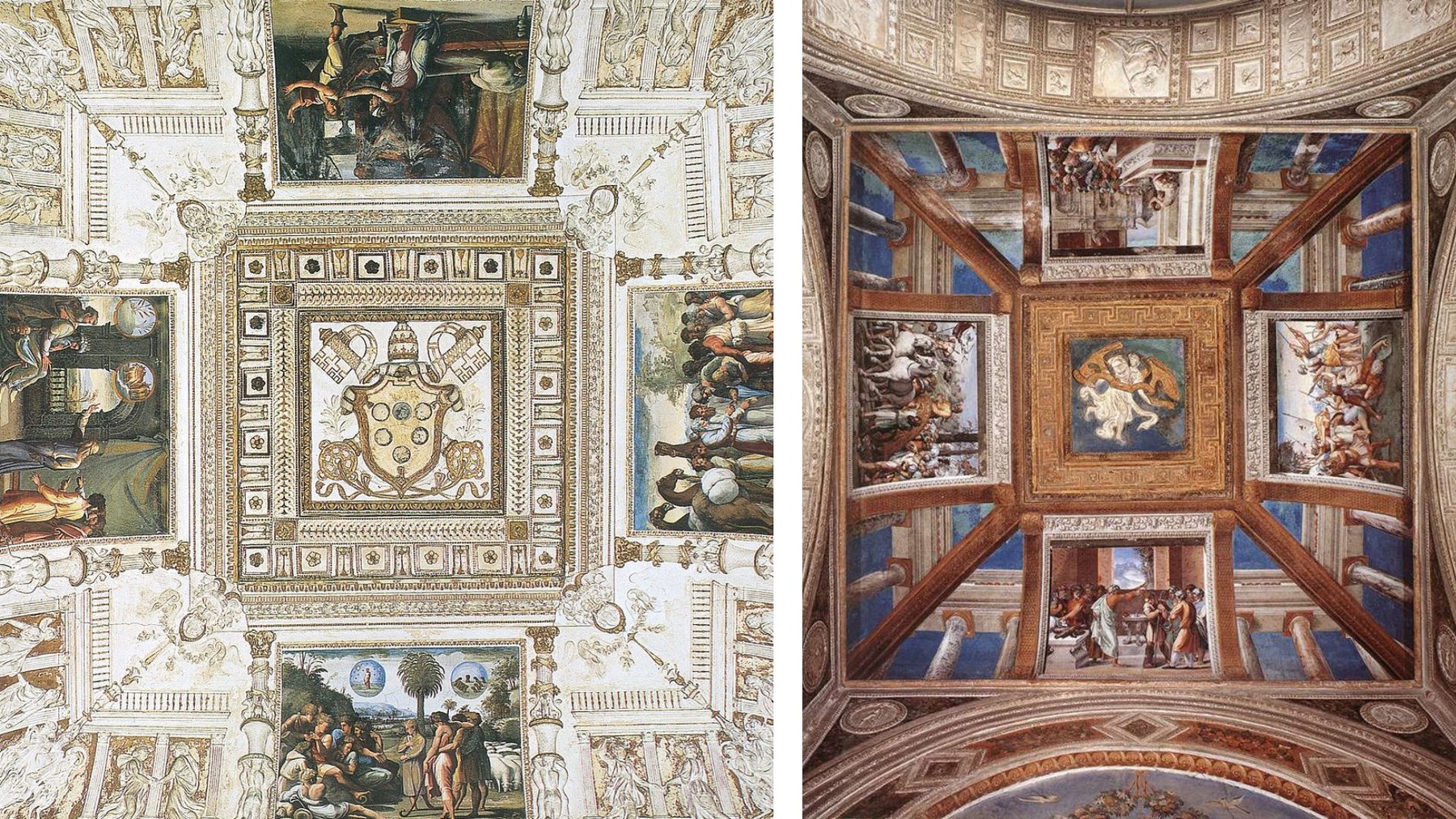

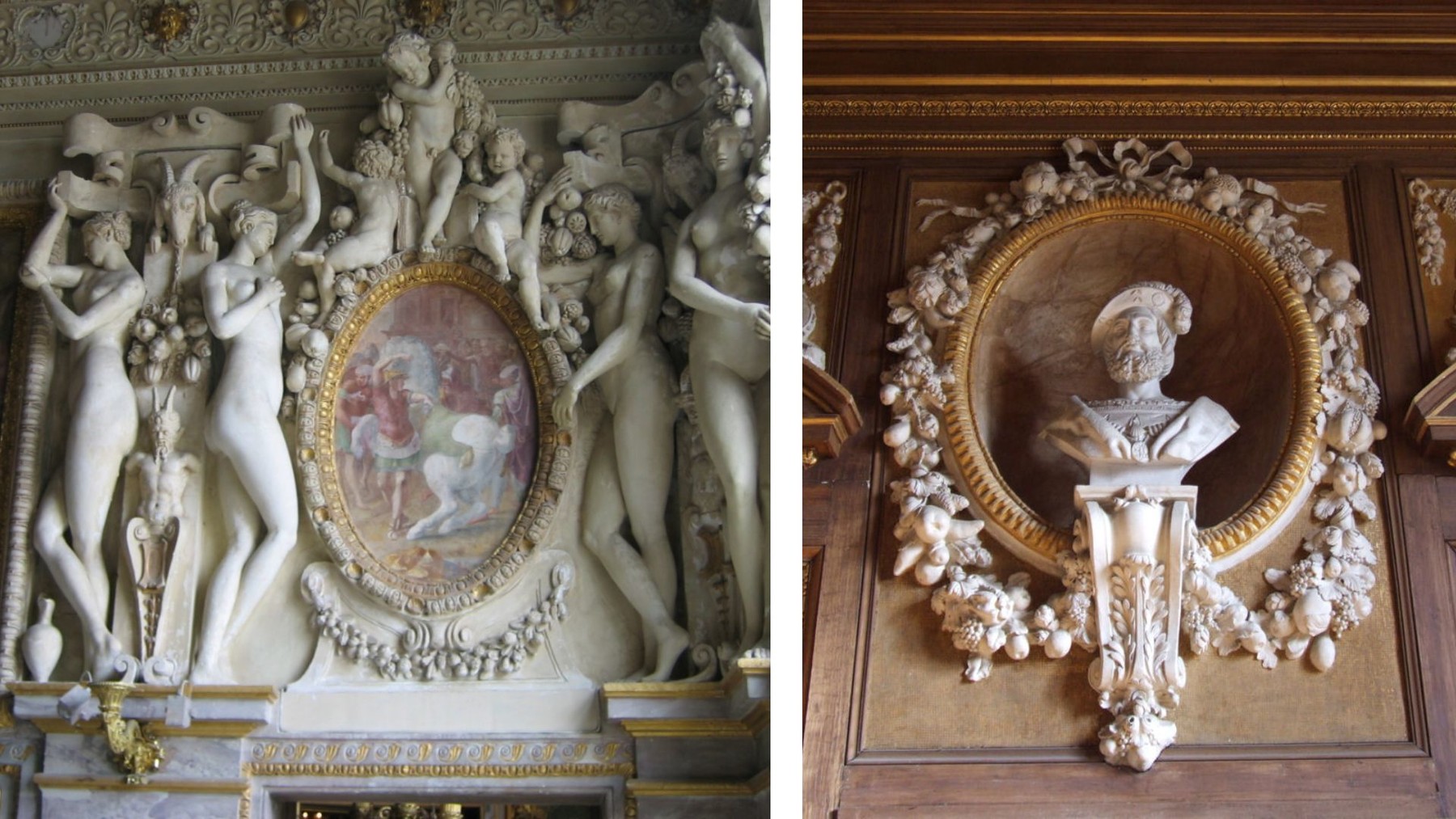

Stucco decoration enjoyed great success from the mid-16th century onward. After the great cycles inspired by the rediscovery of Roman antiquities (Vatican loggias, Rome, c. 1517-1519, by Raffael) and the decoration of Fontainebleau Palace (Francesco Primaticcio, c. 1541-50), stucco decoration spread rapidly through Italy and all Europe.

With just the simple materials of lime, sand and marble dust - and a great deal of skill – the stuccatori could create complex decorations. The technique made it possible to decorate spaces and adapt old buildings to new tastes: quite quickly, easily, and at reasonable cost, three-dimensional stucco sculptures, unlike works in marble, could ‘emerge’ from walls and vaults, with surprising effects.

Why is the stucco technique so important to Canton Ticino?

A great many stuccatori, known for their art throughout Europe, were born and resident in the area between Lugano and Chiasso and in nearby Lombardy. Beginning in the late 1500s and especially through the next century, Rome rose as the propulsive artistic centre of all Europe. Here, men from Lombardy and nearby Ceresio held important roles as architects, master masons, stonemasons, and stuccatori. Skilled in transforming material, the stuccatori from these areas emerged as true masters of the art.

Everywhere, the demand for skilled labour was high: during the late 16th century almost all places of worship had to update their decorative language, as directed under the Counter-Reformation. In Central Europe, following the devastation of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), many churches, palaces and civil buildings required rebuilding.

When returned from these foreign worksites, many stuccatori created important works of art in their birth towns and villages. Besides remaining very attached to their home communities, such works could also be seen as signs of devotion, and testimony to their accomplishments in professional and social prestige.

Stucco

Sometimes named ‘plaster’ in English, fresh stucco, or stucco forte (‘lime plaster’) is a lime-based mixture, highly malleable, that allows the covering of architectural surfaces and the modelling of three-dimensional forms. Once hardened this mixture takes on the appearance of marble.

Stucco is mainly used for indoor decoration. In the rare cases of outdoor use, the stuccatori used additives in their plasters and mortars, or protect the surfaces with organic substances, aiming to improve the strength and resistance of the finished works.

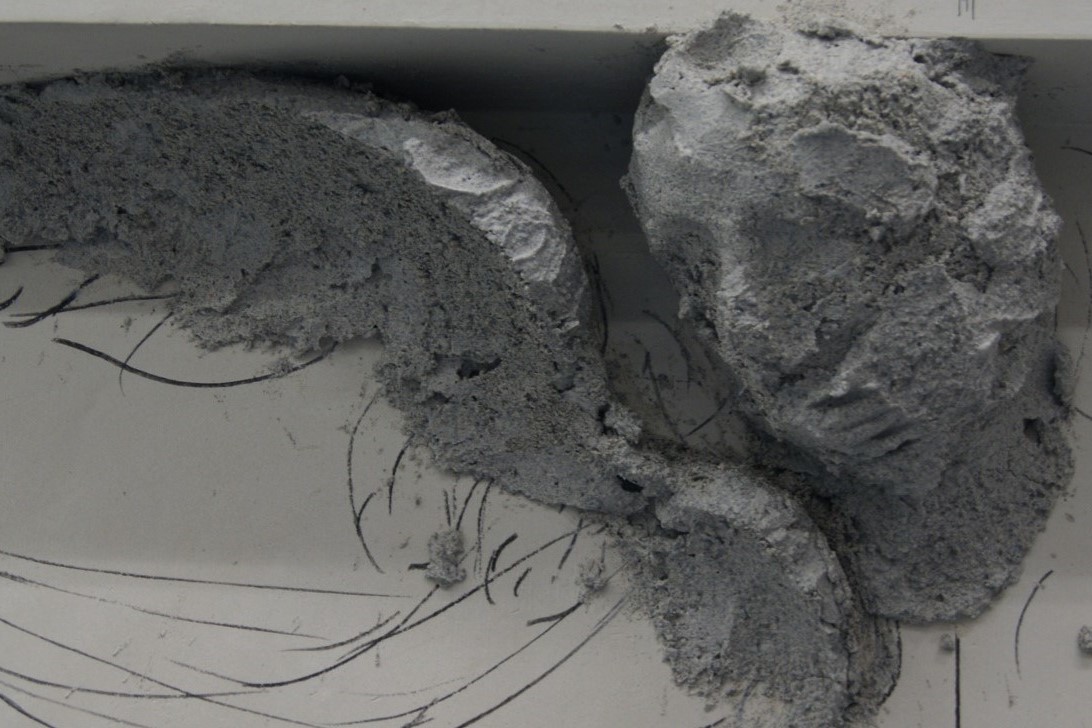

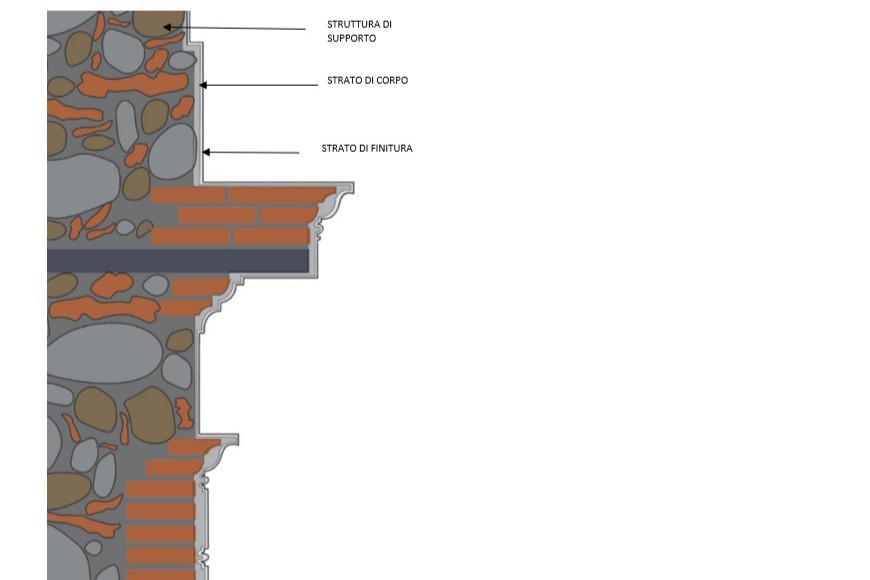

A stucco decoration is usually composed of two layers: an inner or “coarse” coat applied in several layers of a few centimetres, to define forms and patterns, and an outer layer (setting coat) of light-coloured mortar, just a few millimetres thick, achieving a finish with similarities to marble.

There were no ready recipes for making a stucco, no manuals of reference: each artist developed their mixtures according to their own needs, adapting the basic ingredients in respect of the materials available and the character of the worksite. The coarse layer is typically composed of lime, sand, and water, potentially with additives such as gypsum, milk casein or egg. In the case of these latter organic additives, scientists have found it very difficult to identify exactly what the artists used. The additives served in slowing or speeding the setting time, in improving the workability of the mortar, and in avoiding cracks. In preparing their mixtures, the masters had to achieve the double criteria of plasticity and malleability in the fresh mix, but maintenance of form as it cured. Fresh mortar composed solely of sand, lime and water is not ideal for working in three-dimensional forms, particularly in projecting statuary, as it lacks sufficient plasticity, loses shape under its own weight, and risks cracking as it dries.

By carefully selecting among organic and inorganic additives, the master could achieve the desired characteristics for both coarse and setting mortars.

Coarse mortars were prepared in many ways: not only with lime, sometimes also with gypsum; with brick or coal dust; with clay, silica or carbonate sands. The setting layer was generally of lime, marble dust, water, and once again, the potential additives: casein, eggs, oils, soaps, waxes, nowadays all difficult to identify. Today, the original surfaces are also often difficult to observe because of the whitewashings added over the centuries, or because of poor cleanings and ‘restorations’ causing irreparable damage. In spite of this, we are still able to detect many differences in the way the artists composed and worked their finishing layers.

What kinds of challenges did the worksites present?

A master stuccatore, by definition, had to be a good sculptor, a master of working in forms. But the work was not the same from one site to the next: the stuccatore had to prepare his mixtures considering the commission, whether for architectural decoration in lower relief, or more projecting works, up to three-dimensional sculptures. The artist would adjust his modus operandi also in respect of atmospheric conditions, which could be dry, warm, cold or wet. He had more or less to accept the availability of the base ingredients, and adapt to their characteristics. These are some of the reasons why the stuccatori would use organic and mineral additives: to adjust their mortars to all these conditions.

The materials

Stucco decorations are made using mixed materials. Mortars are usually composed of: lime, sand, gypsum and marble powder. The stuccatore could draw on many other materials to provide structural support. Some of the most common were ordinary bricks and very thin ones known as tavelle - irons and nails of various forms and dimensions - rope and tow.

Using these materials, the stuccatore developed a layered form:

– a support structure;

– reinforcements and anchors;

– coarse layer(s);

– setting layer;

– finishing layer.

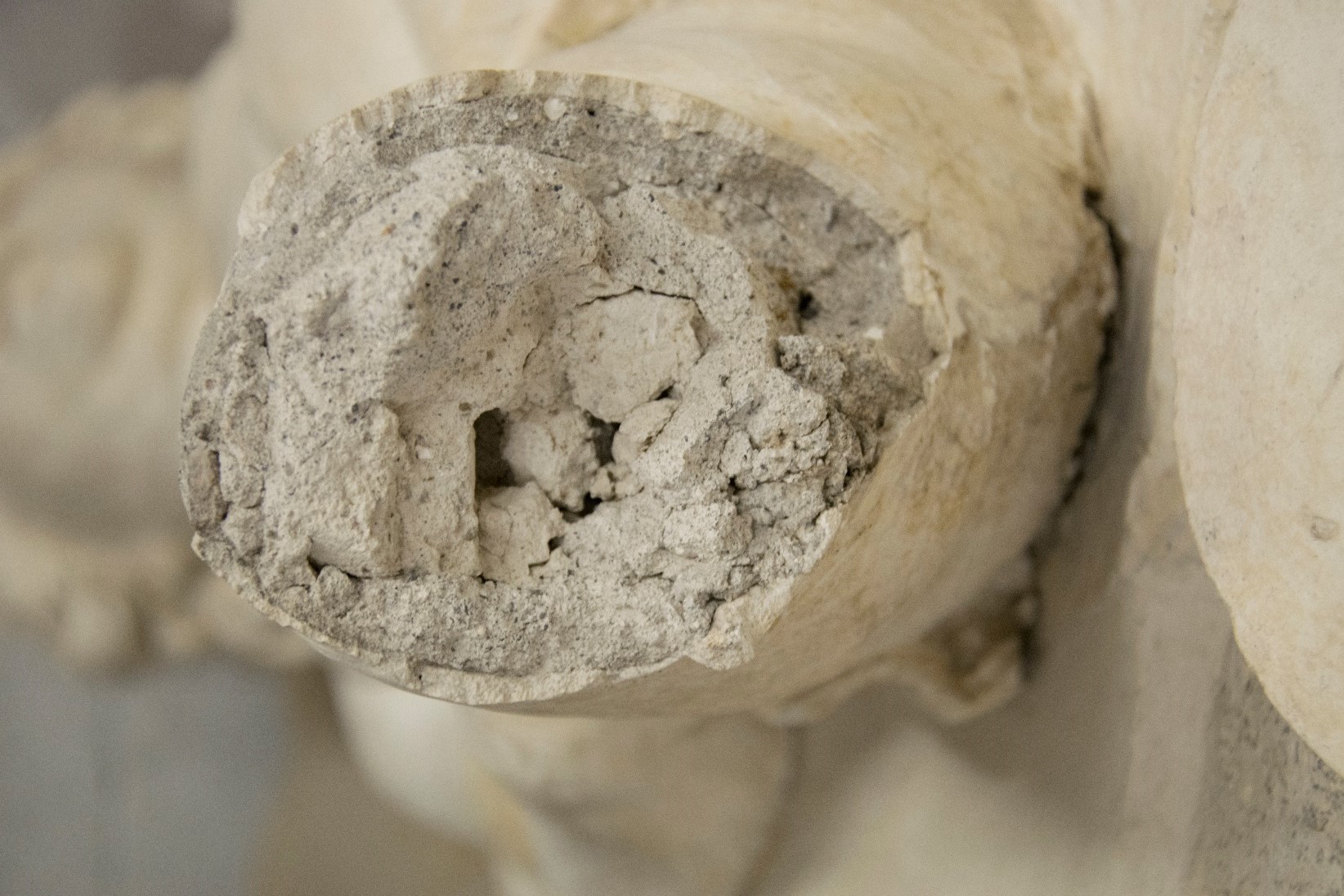

For more imposing forms, before applying stucco, a support structure had to be set up, usually in masonry of brick, stone, or both. This would be shaped to suit the plastering layers.

Large three-dimensional sculptures required supporting frameworks, almost always in metal, selecting from wire, iron rod and bars, sometimes reused from other sources. Given the relative ease of shaping iron, wooden support structures were quite rare. A slender iron bar called vergella could be bent into different shapes, making it very useful in creating the armature for three-dimensional elements. The sculptor could also draw on different kinds of commercially available nails, called da quaranta, da ottanta, da cento, corresponding to the numbers of nails produced from one libbra (about ¾ kg) of iron.

Canton Ticino and its surrounding areas are rich in raw construction materials, also useful in decoration. Kilns produced lime by firing the dolomitic limestones (containing magnesium) typical of local geology. The village of Riva San Vitale was particularly known for operating several brick and lime kilns. Next the waggoneers hauled the lime to the worksites, where it was slaked by immersing in water-filled pits, and left to mature.

The most abundant component in a mortar would usually be sand, quarried locally. The use of this aggregate served in:

– increasing porosity of the mix;

– fostering the chemical reaction of carbonation;

– reducing shrinkage during drying;

– improving mechanical properties.

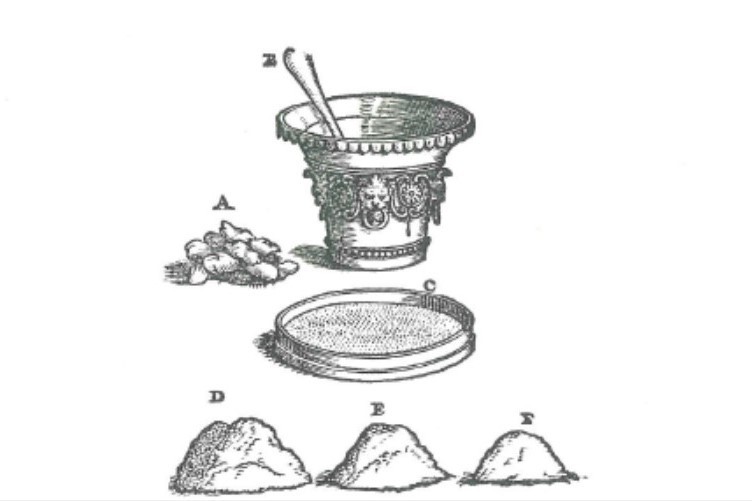

The marble used in the finishing layers usually came from quarries in Musso, along the Lake of Como. Scrap material was sufficient for producing the marble powder: by pounding and sieving to obtain the desired grain sizes.

Organic additives, such as oils, eggs, milk casein and soap, served in rendering the mixes more plastic, in both the coarse and setting layers. Modern analytical techniques are often insufficient to detect exactly what these materials were.

For pigments, metal leaf for gilding and other special materials, the usual source would be the markets of Como.

The tools

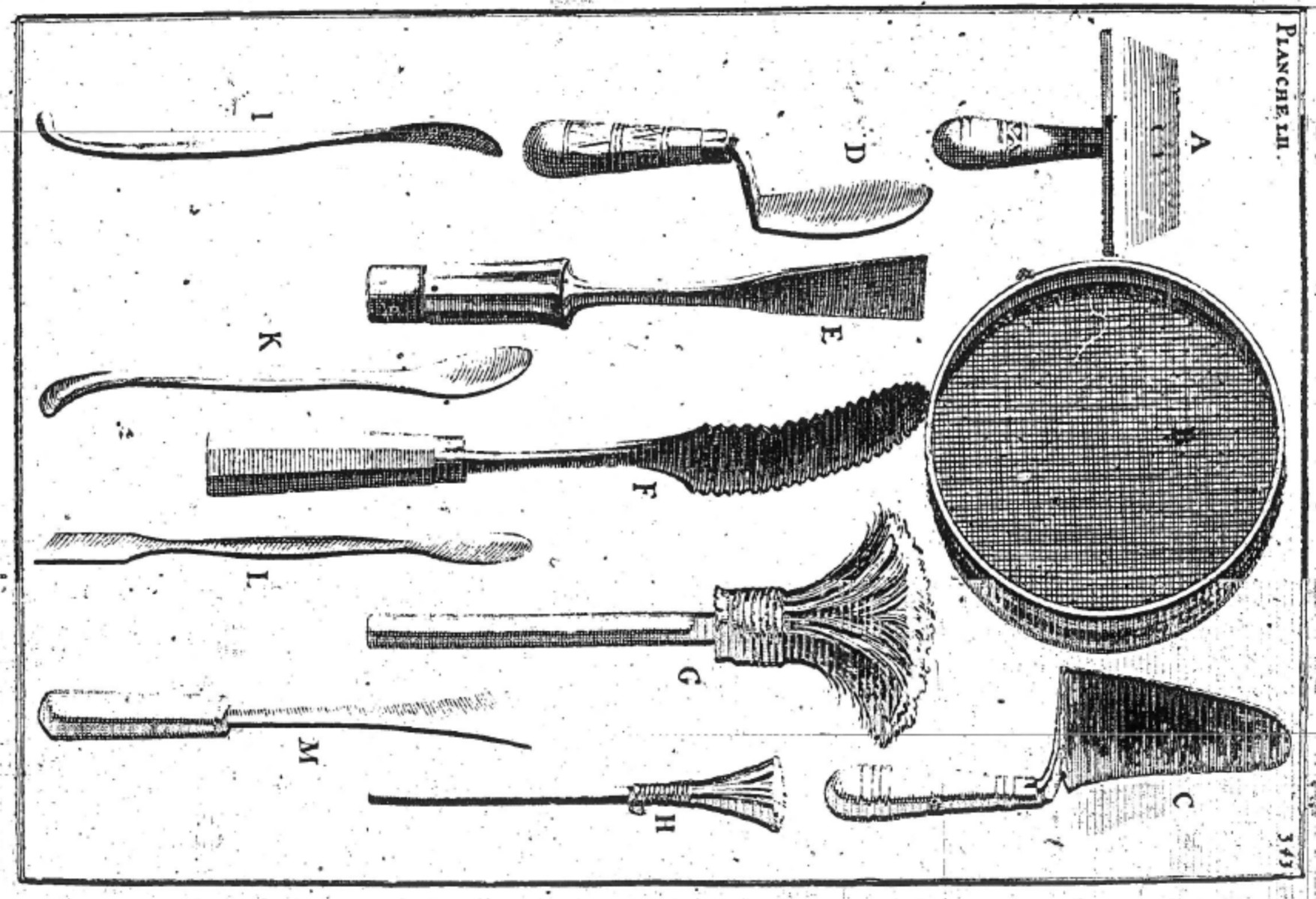

The tools of the 16th-century stuccatore are still used by modern artisans, some 500 years later:

– the ‘hawk’, or hand float, used to hold and carry the mortar;

– wire sieves;

– large and small trowels;

– scrapers;

– broad and fine brushes;

– spatulas (large, lanceolate, large leaf);

– metal templates, for running moulds;

– moulds.

You can see some of the tools used by local artisans at the Museo del Malcantone in Curio

Techniques

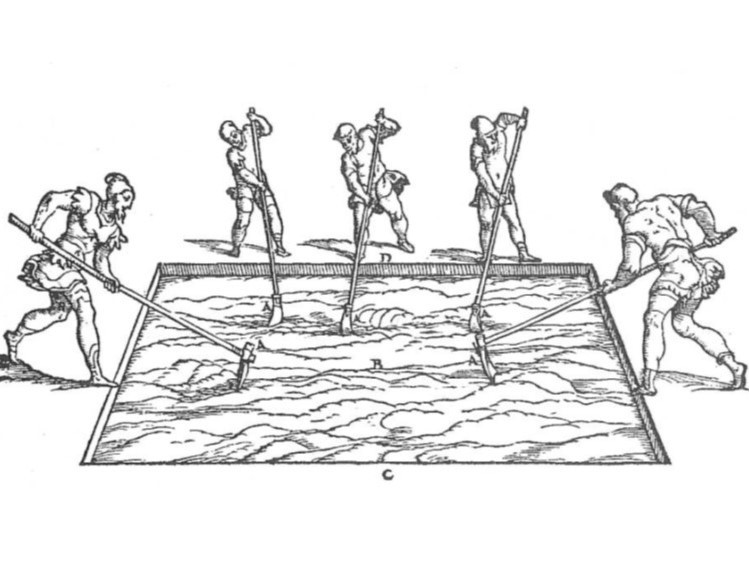

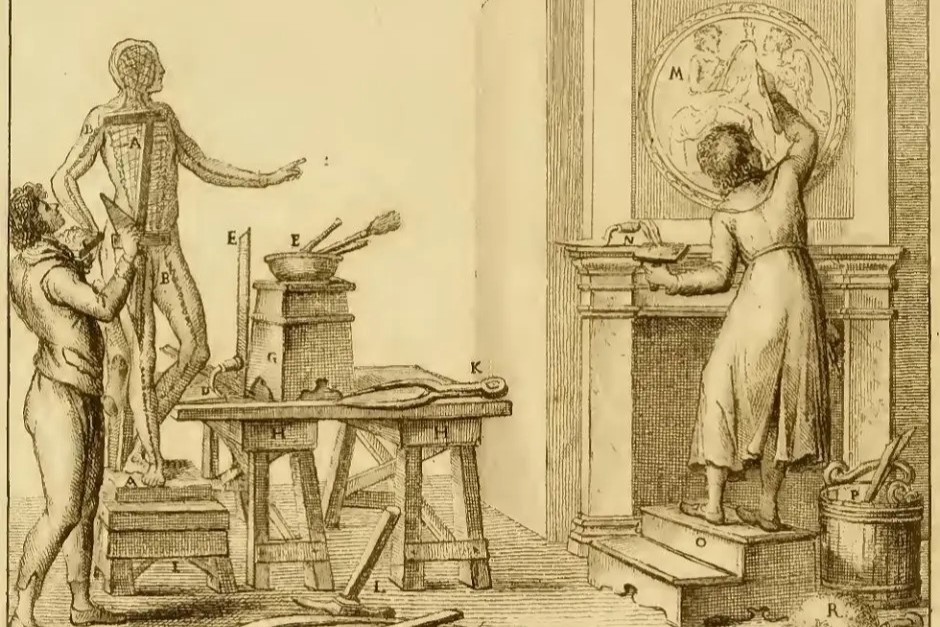

Making moulded frames

Decorative frames on walls and ceilings were made using a profiled form, known as a modene, a term similar to the English ‘mould’, and consisting of a metal template mounted on wooden rails. First the coarse layer was applied along the desired line, a few centimetres thick, then the workers slid the form along the mortar, creating the desired form.

Decorated frames

Decorative elements could be added to the basic forms of the frames, and for this, moulds would often be used, pressed on the fresh setting layer.

Sculptures, projecting in three dimensions

To create sculptural forms, the artist would first sketch the intended shape on the finish plaster of the backing wall. Sometimes they would key the wall with hammer blows, to improve adhesion of the new mortars. Highly projecting works required wall anchors and internal support structures, usually made in iron but sometimes in wood, or even reed canes. For less projecting elements, or bas relief, the artisan could simply insert a few nails. Centuries later, these nails have often rusted, creating weakness in the stuccos. For large three-dimensional sculptures, the sculptor would always prepare a supporting armature, almost always in metal: wire, iron rod, new or used metal bars. Given the relative ease of shaping metal, this was preferred over wood. Under x-ray examination we can see that each artist chose among these materials and used them in their own ways, for the creation of the interior supporting structures.

Special finishes

– Smoothing, by passing tools over the still-wet mortars;

– Polishing, with soap, oil, wax;

– Graining, specially textured finishes, created using brushes, pieces of cloth, spatulas;

– Colouring/painting, for effects of realism, decoration, protection, in fresco technique, or using pigments with binders (protein tempera or oils) on the dried stuccos;

– Patination, for aesthetic purposes and/or protection, using pigments, semi-transparent substances, in fresco, or with binder ingredients on dry surfaces;

– Gilding in very thin foils of gold, silver or gilt tin: the artisan first prepared the surface with a yellow or red layer, chosen to enhance the colour of the gilding, and a primer of gouache or ‘mission’ adhesive, finally the leaf. Where gilding was applied, sometimes it was limited to the most visible parts, with receding areas simply painted in ochre colour.

Bibliography

– Damiani Cabrini L., Le migrazioni d’arte, in R. Ceschi (ed.), Storia della Svizzera italiana. Dal Cinquecento al Settecento, Bellinzona 2000, pp. 289-312.

– Biscontin G., Driussi G. (eds.), Lo stucco. Cultura, tecnologia, conoscenza, Atti del Convegno di Studi, Bressanone 10-13 luglio 2001, Padova 2001.

– Aliverti L., Conoscenza delle pratiche costruttive storiche degli edifici in area lombarda: i manufatti in stucco, in V. Pracchi (ed.), Pratiche costruttive storiche: manufatti in stucco e strutture lignee di copertura in edifici lombardi, Como 2008, pp. 20-91.

– Zamperini A., Stucchi. Capolavori sconosciuti nella storia dell’arte, Vicenza 2012.

– Casey C., Making Magnificence. Architects, Stuccatori and the Eighteenth-century Interior, London 2017.

– Felici A., Jean G. (eds.), Stucchi e stuccatori ticinesi tra XVI e XVII secolo. Studi e ricerche per la conservazione, Firenze 2020.

– Zapletalová J., Swiss artists in Alpine passes...How artists travelled from the Lombard-Ticino lakes to Central Europe, in "Quart", Olomouc 2020, pp. 3-16.

– G. Jean, A. Felici, L. Tedeschi (eds.), The Art and Industry of Stucco Decoration in Europe from the 16th to the Early 18th Century, Roma 2024 (in print).